Azizulhasni Awang pointed the finger at France’s Rayan Helal and the derny pilot in comments following his first-round disqualification from the Olympic keirin competition.

Writing on social media (with the warning that we’re relying on computer translation here), the Malaysian superstar confirmed that his plan had been to claim the front as quickly as possible, as he expected several riders ahead of him to attack early.

With one lap left before the pacer pulled out, I had already started moving forward slowly from behind. The plan was to move forward and be on the outside of the first or second rider, and after the pacer pulled out, I would continue to accelerate to take the front position.

However, when passing the third corner and before entering the fourth corner, I was blocked by pressure from the French rider. The pressure was too aggressive, and for me, it was intentionally aggressive as it caused a collision, and I almost fell. I was saved from falling due to my quick reaction and good handling skills.

Not only that, he was still closely following beside me and kept trying to pressure me from the side. In such a situation, my reaction was to move forward to avoid him.

As an elite Keirin rider, we know the speed for the pacer before they pull out. Usually, on the last lap, the pacer will pull out after passing the fourth corner at a speed of 50-55 km/h. However, in my race earlier, the pacer was moving slower than the actual speed and did not pull out after the fourth corner.

While I was in a tussle with the French rider, I noticed the pacer had not yet pulled out, which surprised me. I tried to backpedal as a way to brake, but unfortunately, I didn’t have enough time to slow down to the desired speed.

According to the race rules, the rear wheel of a rider cannot overtake the pacer before the pacer pulls out at the pursuit line, which is a thin line in the middle of the front stretch (not the starting line).

Did my rear wheel overtake the pacer before the pacer pulled out? My answer is yes, but it was unintentional and due to two reasons: first, the constant blocking and pressure from the French rider, and second, because the pacer was moving at only 40-45 km/h, not at the usual speed, and did not pull out as usual.

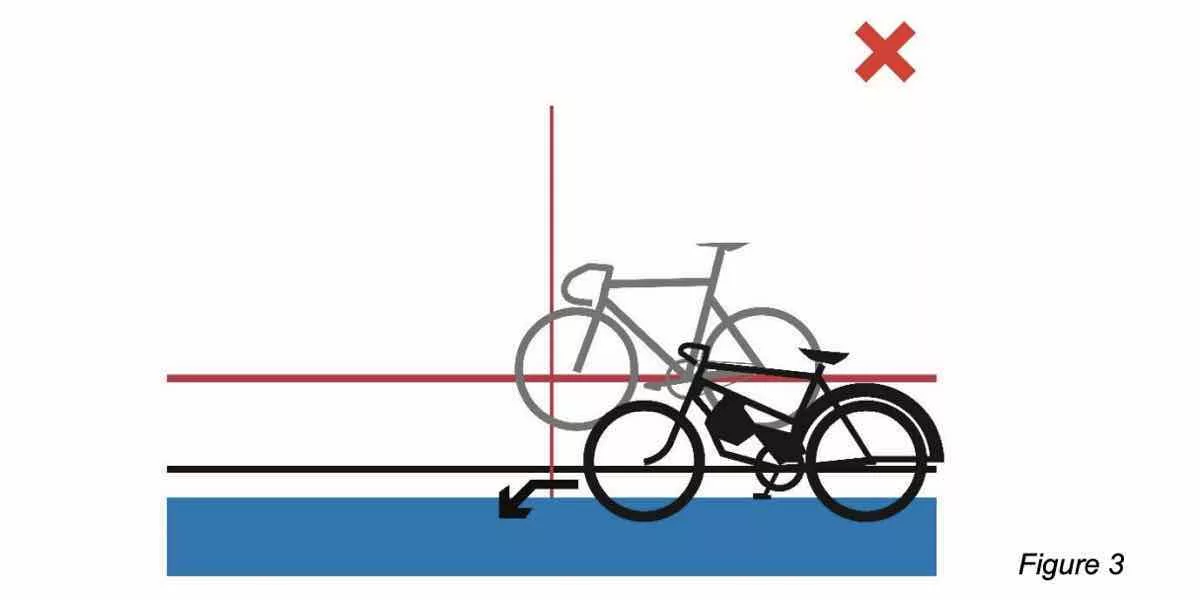

That isn’t quite what the UCI rulebook says, though. Rule 3.2.140, modified in October 2016, talks about ‘riders pass(ing) the leading edge of the front wheel of the pacer’. This is backed up by a series of illustrations, showing that an infraction happens when the front wheel of a rider passes the front wheel of the derny.

Awang also posted a video confirming that Helal had indeed come out of line into corner two, forcing him up the track. But the video also shows his front wheel is well ahead of the derny’s front wheel into the back straight.

It’s conceivable that the commissaires might have accepted Awang’s appeal that he was taking evasive action to avoid a crash.

But with criticism of inconsistent decisions in previous days, and with the memory of Rio’s chaotic keirin final, it’s easy to see why the commissaires would enforce the rule exactly as it is (currently) written. It’s hard to cite Rio as a precedent for leniency, as some have done, when the rule was specifically clarified after Rio.

Awang’s exit has been huge news in Malaysia. The country’s youth and sports minister, Hannah Yeoh wrote on Facebook: ‘For the parents who were watching the race with their children and having to deal with many questions ‘What happened? And why?’, please take the time to explain it to them.

‘It’s not going to be easy, but you must help them process it even as you struggle to accept it yourself.’

She urged people to ‘be kind to Azizul and his team during this difficult time. Especially so for his young family. Be kind with your words.’

But Malaysian fans were quick to accuse the UCI of double standards, and even racism following the decision.