We have written previously about Grand Slam Track, Michael Johnson’s initiative to launch a ‘regular season’ for top-level athletics, filling the gaps between Olympics. There are obvious parallels with DerbyWheel’s plans to do likewise for global track cycling, as DerbyWheel’s CEO James Pope has noted recently on LinkedIn. So what did Global Keirin spot in the first two days of the new competition?

Is that a cycling track?

OK, we’re a cycling operation here, so we got kinda distracted by the first wide-shot of the stadium in Kingston, Jamaica. Event number one is taking place over three days at Jamaica’s National Stadium, known as the home of its consistently overachieving athletics squad. But there’s also a 500 metre concrete cycling track around the outside of the 400m running track. It clearly has seen better days, and it’s probably for the best that it’s largely covered up by advertising.

It happened.

Those of us following DerbyWheel know this can’t be taken for granted. A good proportion of the big names in track competition have signed up to Grand Slam Track, and were present for this first event. TV contracts were in place, with races being broadcast around the world with full production values. Their website has all the results, and there are same-day highlights packages on YouTube from various sources. They hit the ground running.

They came to race.

Credit to the athletes: even this early in the season, they didn’t just show up to claim a paycheque. The first two days have seen multiple athletes setting new personal bests – although that may be because the format requires competitors to participate in events which they might normally avoid. We’ve also noticed numerous tight battles all the way to the line for minor places, which may have been because…

All about the money

At times, the constant references to prize money made Grand Slam Track feel like a Mr Beast gameshow. The total prize pool across the season is US$ 12.6 million, with a minimum US$ 12,000 per competitor, and a maximum US$ 100,000 for the top performer in each category, each weekend – and the cost of being pipped at the line is several thousand dollars at least. There was refreshing honesty from Olympic champion Gabby Thomas, who won the women’s Long Sprints group: ‘I heard them saying on the home stretch ‘$100K on the line’ and it really, really motivated me.’

Empty seats

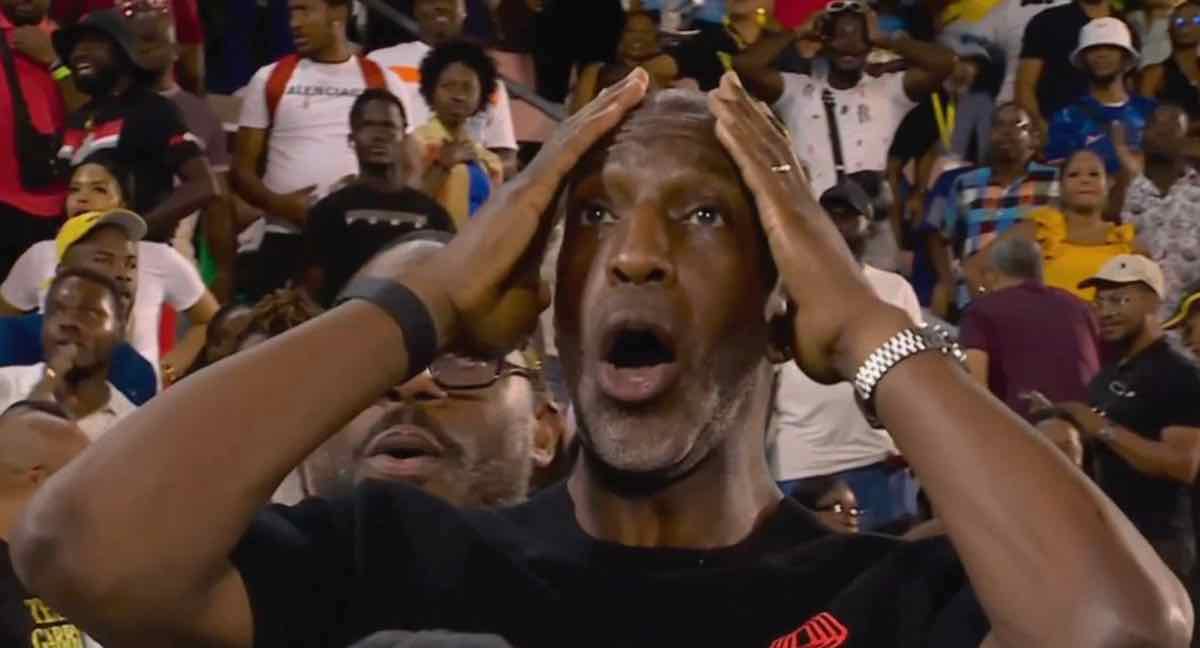

There’s no getting away from it: the Kingston stadium looked empty from most camera angles, with row upon row of unfilled benches. Near-empty arenas aren’t unfamiliar to gamblers in Japan and Korea; and DerbyWheel events will take place ‘behind closed doors’ by choice, the majority of the time. But it sure makes for a flat atmosphere – and any attempt to present the racing to a Western audience must plan for that.

Vuvuzelas

Those who were in attendance made plenty of noise, thanks to the monotonous drone of the vuvuzela – the plastic horns made (in)famous by the 2010 soccer World Cup in South Africa, and later banned by many sports and stadiums. Turns out, we didn’t miss them. But a silent stadium would have been worse.

It’s week one.

Johnson has wisely been balancing the need to hype up the event, with the reality that they weren’t going to get everything right at the first attempt, and that they won’t be profitable for some time.

Presentationally, there’s room for improvement when the series moves to the United States for its three remaining meets. But the bigger challenge over the longer term is making the economics work.

Johnson has described the competition’s recipe for success as ‘the stakes, the stars and the stories’. Grand Slam Track has managed to put two of those three ingredients together: they now need to develop the narratives, whether that’s based on sporting endeavour or dollar amounts, to draw and keep people’s attention.