Japanese keirin is a sport guided by history and tradition; but Japan’s sumo wrestling measures its history in centuries rather than decades. The first written mentions of sumo go as far back as the year 712; it became a professionalised spectator sport in the 1600s.

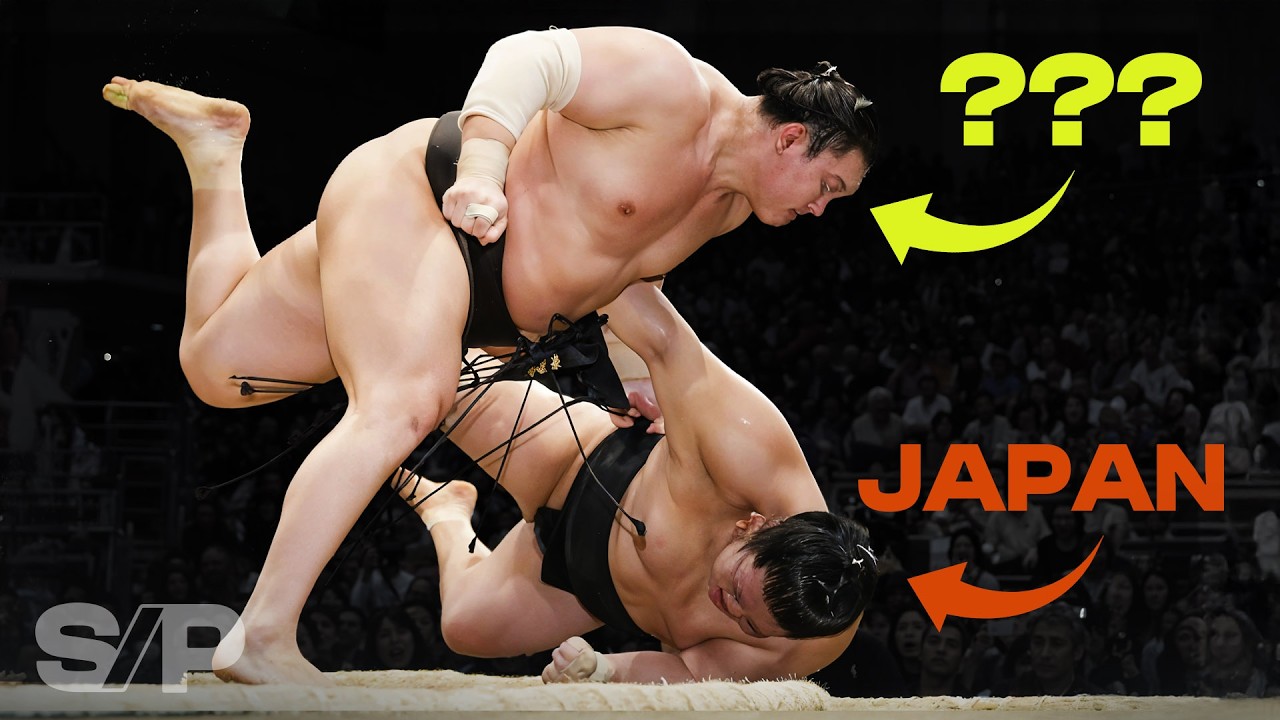

As Sam Ellis explains in a recent video for Search Party, his YouTube channel which often examines the intersection of sports and geopolitics, the recent history of Japanese sumo has been dominated by wrestlers from overseas – and specifically, Mongolia.

He describes how, as Japan became wealthier, sumo went looking internationally for wrestlers prepared to commit to the sport’s demanding lifestyle.

Mongolia’s native wrestling style made transition relatively easy; and with the country’s economy shrinking following the collapse of the Soviet Union, a move to Japan became an appealing proposition.

By 2003, Mongolia had its first Yokozuna, the top rank in the sport. By 2016, they made up 25% of the top division, and almost 100% of the champions. And out of the 10 Yokozuna in the last 25 years, six are Mongolians – including the only Yokozuna currently active.

In War On Wheels, his excellent book on Japanese keirin, Justin McCurry observed that sumo audiences were initially ambivalent towards foreign wrestlers – but that resistance was ‘weakening’. Ellis notes that there had been cultural differences – in a more aggressive fighting style, and celebration of victories – which was at odds with Japanese tradition.

Japanese keirin has invited international riders to compete in the past; and initiatives like the current Keirin Advance series show it remains open to change. But foreign participation has been deliberately restricted: McCurry explains that international guest riders were ‘not allowed to pit themselves against the nine elite SS-class riders – surely the most accurate test of both groups’ ability.’

McCurry reminds us that Japanese keirin’s raison d’être is as a gambling business: and international competition challenges the predictability of Japanese racing. When Japan hosted Korean riders in 2015, he observes, betting receipts fell ‘dramatically’.

‘Keirin’s survival depends on convincing punters that the man and woman in whom they are investing their cash are in no doubt about the rules,’ McCurry writes. ‘”The rules (in South Korea and Japan) are different, so no one really knows who or what they’re betting on when there are riders from both countries in the same race,” one JKA official told me. “The risk of a rider making a mistake and causing a crash, or of breaking a rule and getting disqualified, is too high.”

‘Despite the cautious embrace of riders like Truman, Hoy, Büchli and Bos, fortress keirin remains practically impenetrable.’